“Oh Carolina” doesn’t sound like a revolutionary record. On the surface it’s a sweet, danceable love song, buoyed by a joyous chant harmony, handclaps, a bright piano rhythm and insistent drumming layering the whole number. It’s a fun song, a party record. The kind of song any band would want to cover to get their crowd in a happy mood.

But some songs are sweet and fun and also cause deep tremors in the musical landscape. “Oh Carolina” was a breakthrough track in a number of ways, most notably in that it announced the arrival of two gigantic forces in Jamaican music: the brilliant producer Prince Buster, who helped build the sounds of Ska and Rocksteady music; and a small religious sect called the Rastafari, largely ostracized in Jamaican society, whose philosophy would soon be spread around the world in the music played by several of its practitioners.

In context, “Oh Carolina” seems to me like a cannon shot, fired at the height of the Jamaican independence movement, signalling an artistic explosion that would make an island nation of fewer than 2 million people a dominant force in world music.

* * *

Everything good, the empires said, comes from us. All roads lead to Rome.

By 1960, Jamaica was well on its way to rejecting that line of thinking. An independence movement had been gaining ground since the end of World War II and was just two years away from achieving full autonomy for the nation. As often occurs in independence movements, the art and politics followed each other in rejecting old traditions and embracing the value of what the new nation had to say.

Much of Jamaica’s mid-century musical landscape was dominated by the Mento sound, a local style of music similar to Calypso that featured lyrics dotted with topical subjects and subversive political commentary. But as the 1950’s rolled in, more and more artists were being influenced by the sounds of Rhythm and Blues and Rock and Roll that were emanating from the the United States in general and New Orleans in particular.

In 1959, New Orleans legend Fats Domino recorded “Be My Guest.” It was a minor hit in the States, but it hit Jamaican radio systems like lightning. The song was wildly popular, and the up-down guitar rhythm and swinging horns would become trademarks of a new style soon to develop in Jamaica called Ska.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ff5IYXby3Z4

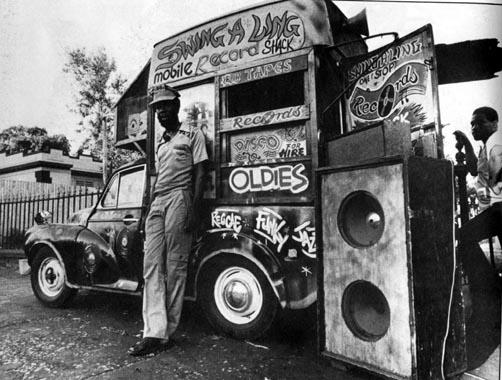

One of the great architects of the Ska scene was Cecil Campbell, better known as Prince Buster. Buster had already established himself in the Jamaican tradition of sound systems, a kind of portable block party featuring a DJ, speakers, and all necessary equipment transported to a party location and set up for a fee. Sometimes they’d be attached to trucks. Sometimes they’d be comprised of stacks of speakers strapped together and forming a wall that blasted songs into the streets. But where the most popular sound systems differed from ordinary DJ’s is that they would play music the engineers had produced themselves. It was live music on tour with a portable radio station.

Prince Buster was unique in this world. Not only did he have his own sound system (Voice of the People), he ran his own record shop (Buster’s Record Shack), wrote his own songs, played instruments, sang, and by 1960, was steadily moving into production of artists. He could make the records, sell the records, and play the records to a crowd, all in the same day.

It was this combination of talents and outlets that would make Buster one of the most important forces in Jamaican music throughout the 1960’s. But it was “Oh Carolina” that jumped that career into high gear.

Early sound system.

Part of Prince Buster’s genius as a producer was in anticipating the directions Jamaican music was ready to take. And one of his most brilliant decisions was to invite a group of drummers from a small community on the east side of Kingston into the recording studio. Their leader was percussionist Count Ossie, and his small community of Rastafarians held ceremonies featuring a type of drumming and chanting that Buster was certain could fit hit records.

It was a bold move. At the time, the Rastafarians were largely ostracized in Jamaican society, and police raids of communities under the guise of cannabis seizures were common. It would be less than two decades before their teachings gained worldwide popularity thanks to the explosion of Reggae supernova Bob Marley. But before any of that, there was Count Ossie and several drummers from his community sitting down in a studio with Prince Buster and three teenagers who had a sweet love song they were excited to record.

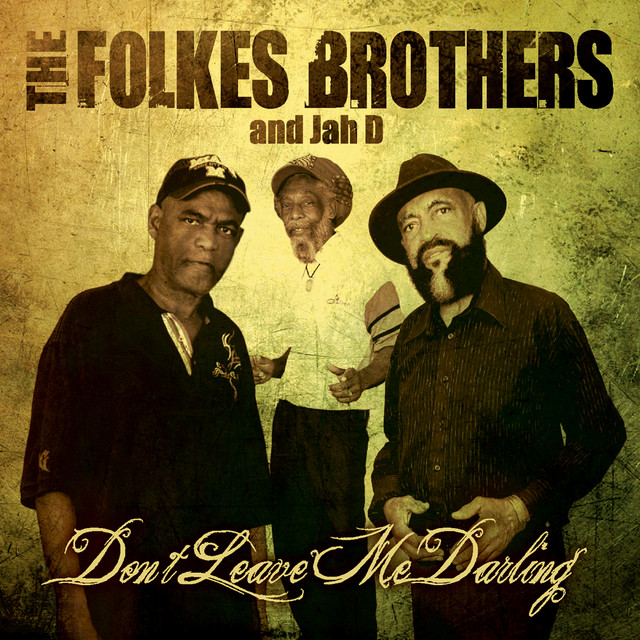

Strangely enough, the only careers that weren’t launched by the release of “Oh Carolina” were those of the three teenagers whose names appeared at on the record. John, Mico and Junior (Eric) Folkes were brought into the studio to record a song that John Folkes had composed outside of his house when he was only 13. It was the only recording the group would make, until two of the brothers reunited to release an album in 2011, 50 years after the first pressing of “Oh Carolina.”

It’s one of the great one-shot wonders in world music. Over the next decade, Prince Buster’s recordings and production would help set the template for Ska music. The following decade would be dominated by the worldwide popularity of Reggae, a style born from the drumming first heard from Count Ossie and his followers on “Oh Carolina.” Ossie himself would become one of the central figures in the growth of the Rastafari movement, and put a permanent stamp on the growth of Reggae with his group The Mystic Revelation of Rastafari. Even Owen Gray, who performs the piano riff that opens the tune, would become one of the island’s most influential performers.

Everyone, it seems, launched a musical career from this record except the man who wrote it: John Folkes.

* * *

Folkes was left bitter by his dalliance in the music business. One of the great catalyzing songs of the century had come from his pen, yet he saw no royalties, and only limited credit. According the Folkes, a 60 pound payment from Prince Buster shortly after the recording was the only money he ever saw.

By 1993, Folkes was a teacher in Canada with a PhD in literature when a former U.S. Marine and Gulf War veteran performing under the name Shaggy recorded an updated, Dancehall version of “Oh Carolina.” Shaggy’s bouncy, bass-heavy cover, featuring his distinctive gravelly voice, shot to the top of the charts in the U.K. But Folkes was again left out in the cold, with the listed songwriters including not Folkes, but Prince Buster (who had inserted his own name onto a number of pressings of the original recording) and even Henry Mancini, thanks to the sampling of Mancini’s Peter Gunn theme on the 1993 version.

A long court case eventually ruled in John Folkes’s favor, though the recognition didn’t pull him back into the music business, as he declined to join his brothers on their 2011 album.

But he now, finally, gets the credit for his song. And while the growth of Reggae and Ska would likely have happened without it, there’s no telling how the arc would have looked. “Oh Carolina” is one of those rare songs in music history that carries the seeds of an entire musical future in its DNA.

“Oh Carolina” wasn’t Mento and it wasn’t Calypso. It wasn’t British or American, rock and roll or rhythm and blues. It was something distinct, a new sound that came from Jamaica, that could only have come from Jamaica. And in its sound you can hear the beginnings of Ska and Reggae, a rhythm and a sound that would throw the engine of empire into reverse. The day would come that Ska bands dominated England, and Reggae was on regular airplay in the United States. The great powers had their ears turned toward Jamaica, hoping to imitate their art. There was no massive radio signal to beam the music across the oceans, nor an armada of publications announcing the trends. There was just the sound of a nation dancing with itself to songs it would teach the world.